A Century In Montrose: From The Corner of Welch And Crocker A Changing World, And A World of Change, Can Be Seen

The two-story gray house at Welch and Crocker looks unremarkable: neither battered nor sparkling, neither historical treasure nor blinding new construction like the townhouses that now surround it. But for just shy of a century, Nell Stewart has watched from its windows as Montrose – and the surrounding world – changed almost unimaginably.

Stewart, now 94, is willowy and limber with crisp blue eyes. From the week she was born, she has lived in this same gray house, first owned by her grandparents, then her parents, and now herself. But Stewart has also lived a great deal on the outside of the house. Decade after decade, she has made new friends as they moved in around her, and has watched the neighborhood’s vertiginous shifts with interest and amusement. That sense of humor has had a lot to do with her ability to enjoy a wildly changing Montrose for so many years.

That humor, and Stewart’s capacity to recall nearly everything.

The helicopter parents of Montrose were on a tear. Every year, the neighborhood schools’ May Fete unleashed a communal mania. Fathers left work early to build giant wooden ziggurats for their children’s performance; mothers of six-year-olds hand-sewed them frocks as if they were readying for the Miss America pageant.

The year was 1930, and nine-year-old Nell Stewart was caught up in the frenzy. The year before, her entire family had gone to see her pose in her new green dress at Woodrow Wilson Elementary‘s fete. This year they would watch her waltz around the maypole at her new school, Wharton Elementary.

But these were different times, long before the self-esteem movement was born.

“Just before the show, the teachers told me and two other girls we weren’t allowed to dance. We were too tall,’’ says Stewart. “At that age, you never, ever forget a wrong. And that is the big grudge I have harbored since grade school.’’

For a woman in her 90s, Stewart is in spectacular form. She moves like someone 30 years younger, navigating stairs and recently climbing unaided into a neighbor’s Jeep. She cleans her house singlehandedly, reads fat history books pressed on her by friends, and does her own shopping alongside a neighbor once a week.

But it has taken more than physical stamina to make the choice that she has: living, unmarried, continuously in one house, in a neighborhood that has careened through more identities than perhaps any other in Houston.

For most of Stewart’s youth, that neighborhood wasn’t even called Montrose. The Montrose subdivision was platted in 1911, nine years before Stewart was born, and the first major home, the Link-Lee Mansion (now a part of the University of St. Thomas) built a year later. But as a community “there was no Montrose,” says Stewart. “The boulevard ended at Westheimer. After that, there was just a dinky little street called Lincoln.’’

There was, of course, a Montrose Boulevard that stretched north from Main to Westheimer, a major artery destined to become a showcase for spectacular mansions, homes to the Cullens, Hoggs, Kirbys, and Rices. But in her early years, Stewart recalls, the area had yet to develop a unified identity. With no Montrose Boulevard where Stewart lived, her community was never referred to as Montrose. Instead, Stewart and her family would say they lived in Southwest Houston. “We were as far southwest as Houston went in those days,’’ she remembers.

There was another official name for the community, though in a hint at the divisions that then scored every aspect of Montrose life Stewart’s neighbors never used it. “Technically, we were Fourth Ward,’’ Stewart says. But even then the name Fourth Ward was associated with Freedmen’s Town, a thriving, dense African-American world of its own with all-black businesses, schools, and family homes. In contrast to the rest of the neighborhood, Freedmen’s Town was on lower ground, plagued by flooding, with shotgun houses that dated to Emancipation, and streets that residents had had to pave themselves.

Five minutes walk across Taft Street would take you into this community. But it was a crossing that, as a child in the 1920s and 1930s, Stewart and her peers never made, physically or in the words they used to describe their world. In her part of Montrose deed restrictions often forbade sales to black buyers, or stipulated that black visitors could only approach by side doors.

“We were all alike,’’ Stewart says in a rueful voice. “We were all the same color and the same middle class.’’ A neighborhood that in later years would be known for its diversity was, in its beginning decades, anything but.

But as in other Southern cities, those rigid barriers were porous enough to permit human connection. Women from Fourth Ward walked or took the bus into Montrose for cleaning jobs; one woman who worked a day a week for several mothers on Stewart’s block often returned for social visits after getting a job at a doctor’s home in the then new River Oaks development.

“We all loved her,’’ Stewart says. ‘’She would tell us children jokes – not dirty jokes, but naughty. She was a preacher’s wife, too. Even after she got that very good job with the doctor’s wife, at a house with azaleas and camellia hedges, she still came to see us. She’d clip some azaleas to bring over without the doctor’s wife knowing.’’

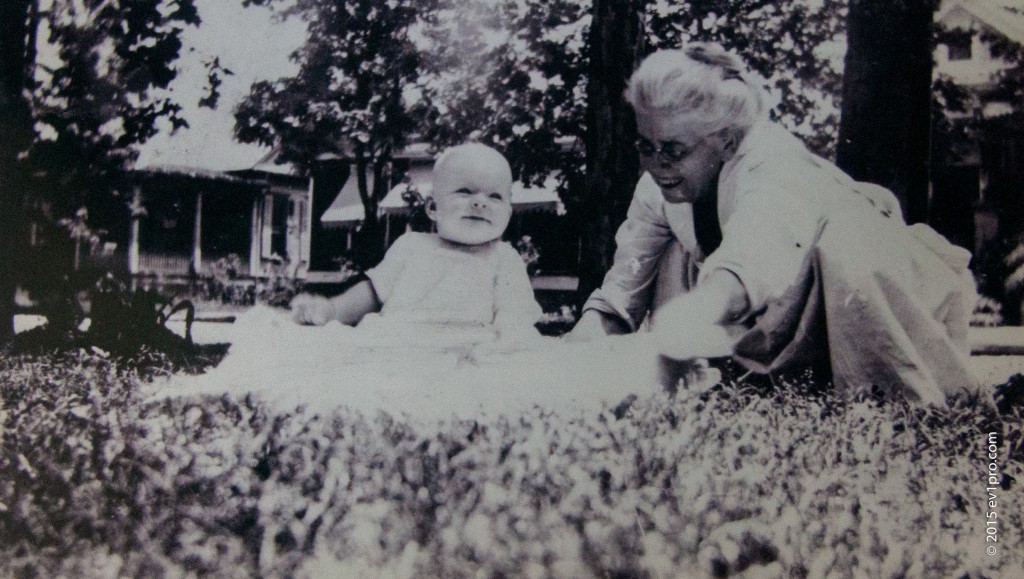

For Stewart and her older brother, life in Montrose was suffused with security. A photo from the early 1920s of Stewart as a toddler shows her cheerfully sprawled on the front lawn: she might well have been left there unattended while her mother ducked into the house to check the oven or confer with a neighbor around the corner. As soon as Stewart was old enough to walk, she began roaming around on her own, popping up on neighbors’ porches or poking through empty lots with her brother and friends.

“We could be gone for hours,’’ Stewart says. “Our mothers probably didn’t know where we were. It was perfectly safe. Nobody worried. There were no strangers: you knew everyone. We’d leave the windows open and the doors unlocked. When we went out of town, we’d leave the back doors open so the dogs could come and go.’’

Stewart loved to walk to Hansen’s grocery store, just a few blocks away at the corner of Welch and Grant, where the owner wrote down the weekly tab every week and reached into the cookie case for Stewart’s purchases with his hands visibly grubby from handling money and moving boxes.

“You would point out your fluffy marshmallow cookie, and he would reach in with his dirty hand. The germs! I often think, that wouldn’t do now,’’ Stewart says. Not that it ever bothered her at the time. Stewart’s mother had come from a farming family that lost everything to the boll weevil and then made their way to Houston’s refineries. Having come from rural poverty, Stewart’s mother loved to indulge her daughter with small treats she had never had.

Then 1929 came.

There was a song that came out then, Stewart says, “In the fall of ’29, you lost yours and I lost mine, but we lost it altogether, in the fall of ’29.’’

The collapse of Wall Street, and the Great Depression that rampaged after it, transformed the country socially and economically. Stewart and her family were luckier than most: her father never lost his job as a pharmacist. But even to a schoolgirl, it was obvious the world had darkened. Stewart heard of rich men jumping out of buildings in New York. Her once-prosperous neighbors suddenly left with their five children to cram into a grandmother’s house in the East End. Homeless, unemployed men knocked on the door pleading for food; Stewart’s mother never turned one away. Years later, Stewart learned that the hoboes had left marks on doorways throughout the neighborhood, signaling which households would offer something to eat.

As Stewart approached college age, it became clear that even her relatively privileged family could not pay for more education. President Franklin Roosevelt saved the day. For young men who needed jobs, he had set up the Civilian Conservation Corps. For students like Stewart he instituted the National Youth Administration, which got her an office job for $75 a semester. Founded in 1935 as part of the Works Progress administration, the NYA three years later was helping 327,000 high school and college students like Stewart get through school. In contrast to the CCC, the NYA served young women as well as young men.

“That’s what got me through the University of Houston,’’ Stewart says. ‘’You never saw the money. The bursar would slip the check under the window, you’d sign it and slip it back. I thought FDR was wonderful.’’

Despite the anxiety the Depression brought, Stewart’s life still had a surpassing innocence to it. “We were so naive – I lived in a bubble,’’ she says. In Europe, violence was stirring. In 1937 and 1938, World War I veterans who had gone back to Europe visited UH and warned about war looming there.

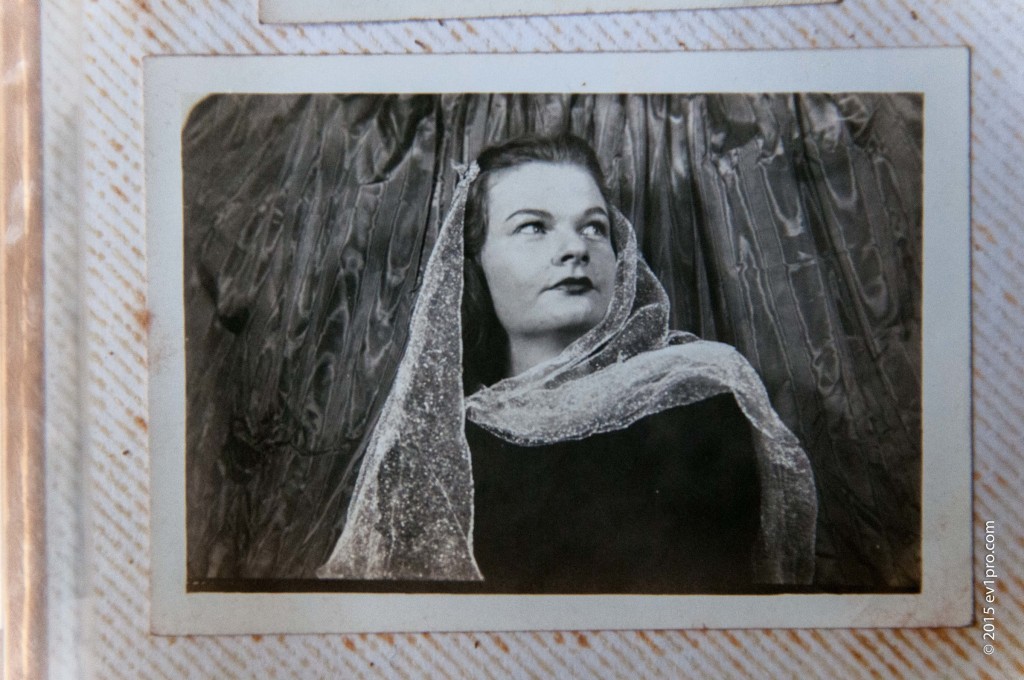

To Stewart, it sounded like they were talking about a movie. She studied art history and didn’t think about making a living; she just liked to paint. She enjoyed living at home, where her mother unabashedly spoiled her. Pretty and opinionated, she had a husband picked out, an ambitious fellow UH student who wanted to marry. But in the end Stewart turned him down.

“I meant to get married,’’ she says. Her voice is light, either because she has no regrets or because the years have worn them smooth. ‘’I was going to be married like all of my friends. But it didn’t work out, and after that I never found another man I wanted to marry. I would never, ever settle. ‘’

What happened?

“He wanted us to go to New York to get another degree. I’d support him and then he’d support me,’’ Stewart says. “Of course we would have had to marry. My mother would have had a stroke. But I didn’t want to go – it didn’t appeal to me. New York still doesn’t appeal to me. I’ve never gone. I wanted to be here.’’

In retrospect, it was that choice – or maybe that assertion of personality – that began Stewart’s journey through what became the many cities of Montrose. For the first two decades of her life, the neighborhood had barely changed. But now, as she settled into what would be her home for life, the chaos of the outside world began to churn through Montrose’s architecture, economy, and population.

The community where everyone looked alike, and everyone was the same, would disappear, to be crammed with factory workers, settled by GIs, colonized by hippies, and tidied up by recovering alcoholics. It would rollick with club kids, get beautified by gays, and once more be filled with placid, affluent families. In the seventy years after World War II, fully a dozen different cities would occupy the landscape of Montrose.

Nell Stewart, by staying put, would live in them all.

This is part one of a series. Part two, The Montrose Century, can be found here.

Oh My Gosh!! What a most beautiful story of a remarkable lady! ❤️ I have lived in Montrose for only 4 years and love it. Own a home from 1937 and wish I had the history of it. I enjoy hearing stories from my neighbors of the area in which they have lived for nearly 30-40 years. Very few of them tho.

May God Bless you Ms. Stewart❤️

Extraordinary! I’m so glad there are still residents like Nell Stewart in the neighborhood! What a great look back, can’t wait for “the rest of the story”!

What a great story. Thank you for sharing. Looking forward to the next installment.

I love this story! I can’t wait for the rest of it!

What a beautiful story of a beautiful lady. I would love to sit and have coffee with her and hear more. She brings the history alive. Thank you for publishing this.

My aunt is so remarkable and I’m glad readers are getting a glimpse of why. Whenever I feel a little down I can call her and I feel encouraged and cheerful. She remembers the shorthand she learned, yet can operate a computer with windows 8 on it. She researches things on the Net, from which doctor is best to tracing her roots on ancestry.com. I love her so much.

A great article about myremarkable aunt.

She is a remarkable and fascinating lady. I am so appreciative to Helen for introducing her to me.

How lovely to hear this story of a lifetime in the neighborhood I have always known as Montrose. Growing up in Spring Branch in 1959, every mother’s dream,a suburban enclave far removed from the downtown area where I was born…great schools and everything NEW, safe.

So now its 1971, a girl and a car and the discovery of the rich, slightly dangerous and NOT new Montrose Blvd, with head shops, The Hobbit Hole for smoothies and avocado sandwiches, vintage clothing, and always something new to discover, recycled clothing, leather shops (my first leather fringed bag) jeans and a feeling of discovery… Herman Park at 5am after a night where sleep or safety were inconsequential because we were watching the sun rise over Sam Houston and life was a discovery to be had.

Deonna, Trish, Debbie, Kerry and freedom freedom freedom. This Montrose shared it’s history, shaped my love for discovery and opened my eyes to the beauty of how the old informs the new. Thank you Houston, Montrose, The Heights and all that exists for an available mind.

Sheri

Fantastic! I love hearing about the history of my neighborhood, especially from someone who witnessed nearly all of it.

My daughter found this article and emailed to me, mainly because she thought it to be a lovely story, which it is. But the irony is, my father grew-up on Welch St, on the East side of Montrose, where he lived with his Mom, Dad & 2 siblings. I believe the oldest child, my Uncle Richard, would have been born in 1923, while my Dad was born in 1928. My Aunt Jane would have been born in ~1925? I wonder if Nell remembers any of the Lucas family? Would really be curious to know. Thanks, Richard Lucas

Yes, I certainly do remember Richard Lucas. He was my classmate at Wharton School. I assume this is your uncle.

My parents were living on Jack Street near Alabama street when I was born in 1943. I lived in Montrose, off and on, until 1972. I’ve lived on Jack street, Banks street, Portsmouth street and again on Jack street. I loved the area and miss the late 1960’s and early 1970’s the most.