The Neighborhood Astronaut: Koichi Wakata Lives In Montrose, But He Works In Outer Space

As a five-year-old in Tokyo, Koichi Wakata watched the Apollo lunar landing on TV with awe and longing. He yearned to go to space one day himself. And he knew it was impossible, because Japan at the time had no space program.

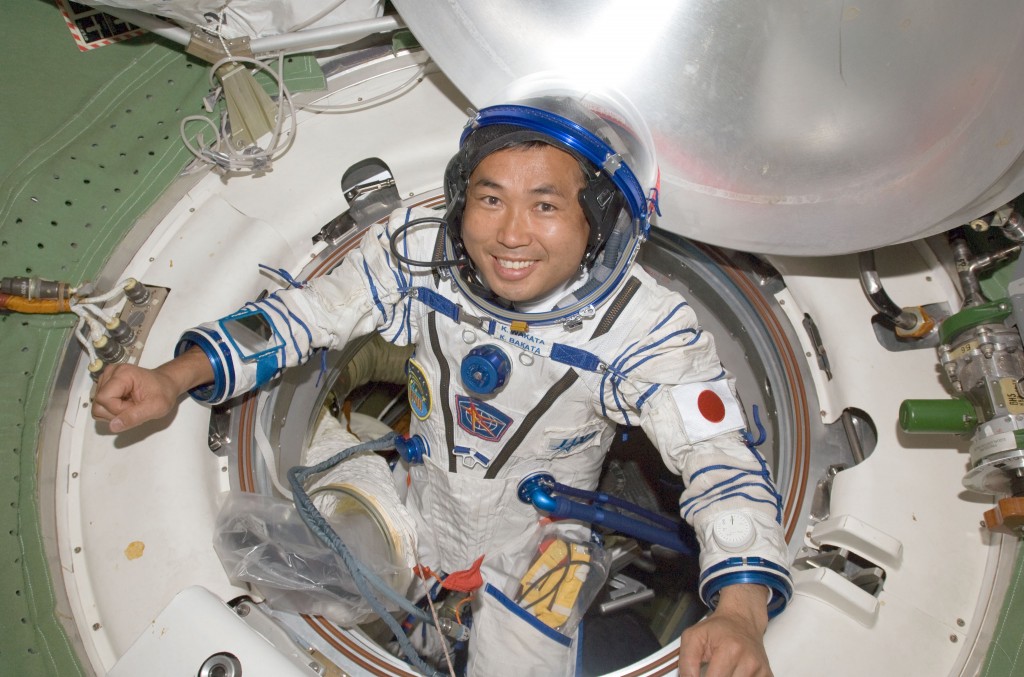

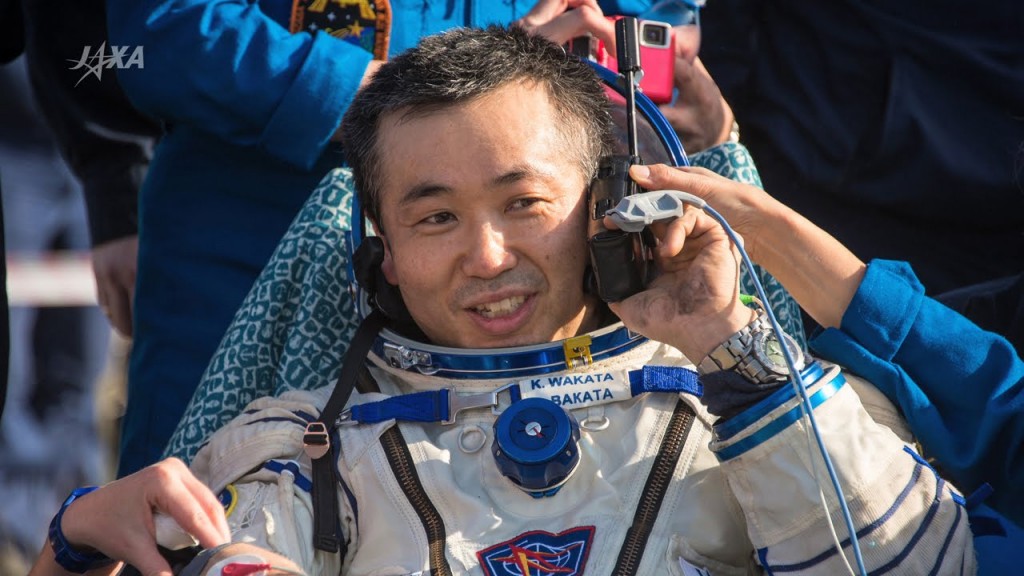

Today, Wakata is the first Japanese astronaut to live in space as part of the International Space Station (ISS) crew. Altogether, Wakata has spent just 18 days shy of a year in space, including four space shuttle missions, a Russian Soyuz mission, and two long-term ISS missions, one for four and a half months, and one for six months. In March of last year he became the first Japanese, and only the third non-American or Russian, to be the ISS Commander.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Wakata has put a little distance between himself and NASA’s Johnson Space Center while he’s on the ground. We began by asking how that happened.

When you’re on Earth, you live in Montrose. How did you choose to live here rather than Clear Lake?

We enjoyed living in Clear Lake for about 18 years as our son was growing up. My wife and I became interested in living in the city; we looked around, and found the Montrose area to be a diverse, fun neighborhood. We moved after our son graduated from junior high. There are a lot of cultural activities going on nearby – so many good restaurants, theaters, museums, fun events. I often go jogging on Allen Parkway, and enjoy the view of the newly landscaped park, the bayou, and the skyscrapers downtown. We really enjoy the atmosphere here, and our neighbors.

Do you have a favorite memory or experience from your time in space?

Often, when you do something for the first time you remember it forever. On my first space flight in January, 1996, we launched at 4:41 a.m., before dawn. When I first saw the shining blue planet shortly after sunrise on orbit, like a blue oasis – the whole planet looked so magnificent. It was beyond description.

What are your NASA duties when you’re on Earth?

Between space flights, when we’re not in the training flow as an assigned crewmember, we support our space programs as representatives of the astronaut office. To date, I have worked on the development and operational support of science payloads, software verification, robotics, space walks, and a variety of onboard systems of the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station. Currently, my duties are focused on operations support for ISS procedures and cargo supply vehicles to the ISS, as well as being capsule communicator, or cap com, the primary contact for communications with the crew onboard the ISS from Mission Control in Houston.

How many space flights have you been on?

I flew four times in space. The first time in 1996, and then in 2000; those were space shuttle missions with a flight duration of less than two weeks. The majority of my training for these flights was in Houston. My third flight, in 2009, lasted four and a half months, and last year I spent six months on the ISS. For the long-duration flights we have training not only in Houston, but also in Japan, Canada, Germany, and Russia.

What did you do on your long-duration missions?

Six years ago, when I was on the ISS for four and a half months, I was involved in the assembly of the space station and a variety of scientific experiments. We installed a U.S. solar array structure and completed assembly of the Japanese laboratory called Kibo.

When I flew last year, the ISS was already in full utilization for science experiments, and we devoted our time to experiments and maintenance. We conducted a variety of experiments in life science, medicine, fluid and material sciences, and engineering.

We have a busy schedule. During the work day, every minute is packed with different tasks. We do have some personal time in the evenings and on weekends. We read e-mails and make phone calls to family and friends. During our time off we can also read books, watch movies, and listen to recorded TV/radio programs. Once a week, usually on weekends, we have a video chat with family at home.

Tell us about your background.

I’m a Japanese citizen, and my employer is the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA. I was born in Saitama, a city north of Tokyo, in 1963. I grew up, went through elementary school, high school, and university in Japan, and received a master’s degree in applied mechanics and a Ph.D. in aerospace engineering.

In 1991, I was working as a structural engineer for Japan Airlines and read about astronaut selection in the newspaper. Back in 1984 President Reagan had proposed that NASA and partner countries build and operate an international space station, with the U.S., Canada, European countries, and Japan being involved. NASA invited the participating countries’ space agencies to send candidates for astronaut training. The class of 1992 consisted of 19 Americans, two Canadian astronauts, three European astronauts, and one Japanese, who was me.

When did you know you wanted to be an astronaut?

When I saw the Apollo 11 lunar landing, when I was five years old. I remember having a strong longing for flying in space. But at the time there were only American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts; I thought it was beyond my reach. But thanks to NASA and the international cooperation in the ISS, I was able to go through the training at Johnson Space Center (JSC).

How did you prepare?

We started astronaut candidate training in August 1992. After completing the basic training, I was qualified as a Mission Specialist astronaut in 1993. The majority of the astronaut candidate training was conducted at JSC, though we also visited other NASA centers and both Air Force and Navy bases.

In the beginning it was a huge challenge for me, especially due to my limited English skills at the time. But the curriculum designed by NASA was so excellent that I was able to get my qualification as a Mission Specialist.

Why were you selected to represent Japan?

That’s a good question. I’ll have to ask my bosses at the selection board. At the time we had about 400 candidates. Working as an engineer was helpful, but since I did not have the operational experience – I really don’t know. The nine-month selection process started with academic exams in different subjects followed by several interviews – psychological, psychiatrical, English language, and management. We had extensive medical tests in Japan as well as in Houston. I was fortunate to be selected.

Where did you learn your flawless English?

I’ve been in Houston for 20 years, and I still cannot speak with a Texan accent.

In Japan we have mandatory language classes that we have to take in junior high school and high school, but the focus was on reading and writing, as we didn’t have many native English speaking teachers.

When I was in junior high and high school, I listened to English language learning programs. I also listened to the U.S. Armed Forces radio broadcasts. I was an exchange student when I was 13 years old, for one month, in Boulder, Colorado. At the time I didn’t speak any English. After four weeks I still didn’t do well. But it was a good eye opener for me. Once you learn the skills to learn a foreign language, you can apply it to a different language.

Crewmembers who fly onboard the ISS need to go through training in Star City, Russia. In the ISS program we have two operational languages, English and Russian. Before starting my technical training for space systems in Russia, I had Russian language immersion training for six weeks, staying with a family and having lessons from Russian language professors in Moscow four to eight hours a day.

You were the youngest astronaut on the space station, right?

I was the youngest in my class of 1992 astronaut candidates. I was 28. At the first astronaut office meeting after we started our training, they gave me a pacifier that had a tag, like the kind on the controls on an airplane, that said, “Remove before flight.”

How did you cope with being in a small space for so many months?

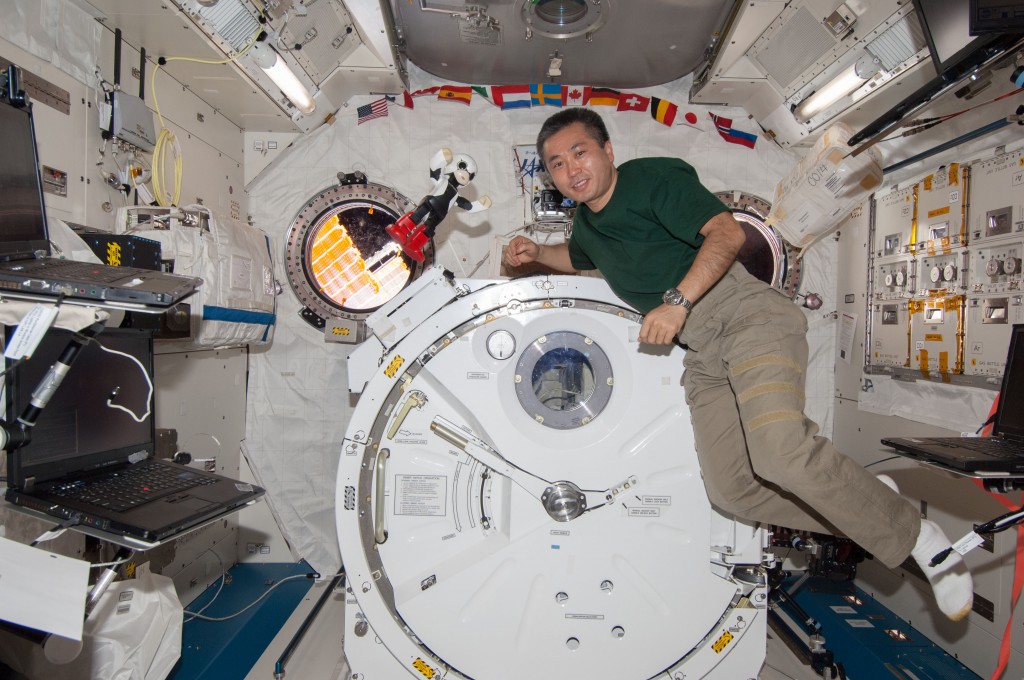

The interior volume of the ISS is pretty big. It’s one and a half times the size of a Boeing 747’s cabin. I used to live in a really small apartment in Tokyo, so the ISS was a comfortable space for me.

There are six crewmembers living and working together. We help each other all the time. I never felt the internal volume of the station was too small for us during my six month stay on the ISS.

What were your quarters like?

We each had our own crew quarters. It looks like a small cabinet, or a telephone booth. It’s very comfortable to sleep in zero gravity – you don’t feel any pressure on any part of your body. In zero gravity you float when you sleep.

We get together for meals in the U.S. Unity module or in the Russian Zvezda module, where we have food warmers and dinner tables. In addition to the research laboratories, habitation modules, and stowage modules, we have docking compartments and a viewing room called the Cupola with seven large windows. The view of the Earth is simply magnificent.

Did you eat only freeze-dried food?

The standard food items we have are freeze-dried, thermally stabilized, or canned. We don’t cook meals. We add hot or cold water to the freeze-dried food, and we warm the thermally stabilized and canned.

We have standard food items from NASA and from Russia, and each of us had some allocation to take up a food preference. The Japanese cargo supply vehicle brought up a lot of Japanese food. I enjoyed cooked fish, rice, and miso soup – they were very popular among my crewmates. Life in space sometimes gets stressful. Getting together for dinner on Friday or Saturday, sharing food, whether it’s Texan, or Russian, or Japanese, is quality time for us. It’s like having a family dinner together, and we cherished the time.

How much exercise could you get?

We are allocated two and half hours of exercise time every day. If you stay in zero gravity for many months and you don’t exercise on a regular basis, you will lose bone density much faster than osteoporosis patients on the ground. On the ground, the older we get, the more susceptible we are to osteoporosis. But in space, regardless of your age or sex, you lose bone density and muscle strength, especially on your lower body, unless you exercise.

We use a resistive exercise device for muscle strengthening as well as a cycle ergometer and treadmill for aerobic exercise. Since we are in a weightless environment, we cannot use weights for exercise, so we use resistive force created by vacuumed cylinders. Usually I spent 40 minutes for aerobics exercise and a little over an hour for resistive exercise every day.

What research did you do?

More than a hundred experiments in such areas as human physiology, life sciences, fluid physics, material processing, and engineering were conducted during my six-month flight. One of the experiments that I worked on studied convection of liquid caused by surface tension. The results of this experiment will help improve production processes of semiconductors and heat radiation devices of small electronics.

I also worked on protein crystal growth experiments for the development of new medicine to cope with muscular dystrophy and vaccinations that could work against different types of influenza. High quality protein crystals grown in microgravity aid in analysis of the protein structure, and pharmaceutical companies are becoming involved in using the space environment to develop medicines. Other experiments I was involved in include a combustion study in zero gravity that can be utilized to make better performing jet engines, as well as a study of ice crystal formation that could contribute to the development of technology to help keep human organs viable for organ transplant.

Did you work on any behavioral or psychological experiments?

The stressful part of a space flight comes from living in an isolated environment for months, separated from family and friends as well as our colleagues in Mission Control. Sometimes communication could be difficult. We all know that.

If you have been in one place, like maybe a submarine for some time, you’ll encounter the same situation. Communication is the key, and always thinking of “we” and not “they.” The weekly video chat with our families and friends is a great psychological booster.

When we go to Mars we will not be able to carry on easy audio or video conversations, because the time delay for a signal could be as long as 20 minutes. Onboard the ISS, if we have a question we can always ask the ground, and we can receive an answer right away. Since this kind of real-time communication won’t be available on a Mars mission, the crew will need to be more autonomous. And communication via recorded voice or video and texting or e-mails could add psychological stress during a two-and-a-half year flight to Mars.

Have you ever tired of being in space for such prolonged periods?

On the ISS, every day is different. We work on a variety of experiments, maintenance tasks, spacewalks, robotics, Earth observation, public appearance and educational events as we circle the Earth 16 times a day. During my flight last year, we went around the Earth more than 3,000 times. Each time we fly over a certain area, the view is different. You never get bored.

What’s next for space travel?

The development of commercial spacecraft is underway, and will start taking us to the ISS in a few years. NASA’s Orion spacecraft successfully completed a flight test last December. It’s exciting to see the development of the Orion and the new rocket that will take us beyond low Earth orbit, where we have the ISS, to destinations such as the asteroids and eventually Mars. I personally would like to see us go back to the Moon.

Space exploration has become an international effort, and reminds us that we all share one planet. Whenever different nations come together to work on common goals there are challenges to overcome. But the final product is a remarkable example of pooling visions to advance the human race in a peaceful manner.

Hello! I’ve been following your web site for a while now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Houston Texas!

Just wanted to tell you keep up the fantastic job!