The Values Game: Montrose Media Developer Helps Guide Medical Students Through Ethical Issues

Wayne is a hypochondriac.

Walter is drunk.

And Sheila is having an affair.

Meet the Brewsters – not the heirs to Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, but a fictional Houston family created to help instill ethics in future healthcare professionals. They do this through The Brewsters, a deceptively playful ”choose your own adventure” novel about the length of Stephanie Meyer’s teen vampire epic Eclipse.

In The Brewsters, a product of the Montrose-based Archimage, readers follow the stories of several healthcare students working with the three-generation Brewster family. When the characters face ethical conundrums, the reader must make choices for them: Should she indulge Wayne Brewster’s demand for a needless bone scan? Let medical student Walter Brewster drive tipsy? Help mother Sheila Brewster get birth control for her daughter – but lie that it’s only for acne? When the reader flips to the page describing the outcome of her choice, it’s clear that just as in real-life medicine, seemingly slight decisions can have momentous results.

Until about four years ago, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, like most health science centers, taught ethics in the classroom. Medical students took medical ethics, dentistry students took courses in dental ethics. All learned the basics of relevant law, and memorized their fields’ ethical codes. UT Health students reported satisfaction with their studies, and felt confident that as a result they would be able to make good ethical choices.

The only problem was that their actual ethics test scores were dismal. According to a 2014 article in Nursing Ethics, a ten year study of UT Health students, ”revealed that they had difficulty even identifying ethical dilemmas, and few students could describe the application of ethical codes or principles in their ethical decision-making process.”

UT Health attacked this problem with an ambitious plan: required first-semester, interdisciplinary ethics instruction for all health profession schools, at all degree levels. But the teaching clearly needed to differ from the established lecture-and-PowerPoint formula. Led by professor Jeffrey Spike, UT Health’s McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics launched a project to create something new, an approach riveting enough to engage students not just intellectually, but emotionally.

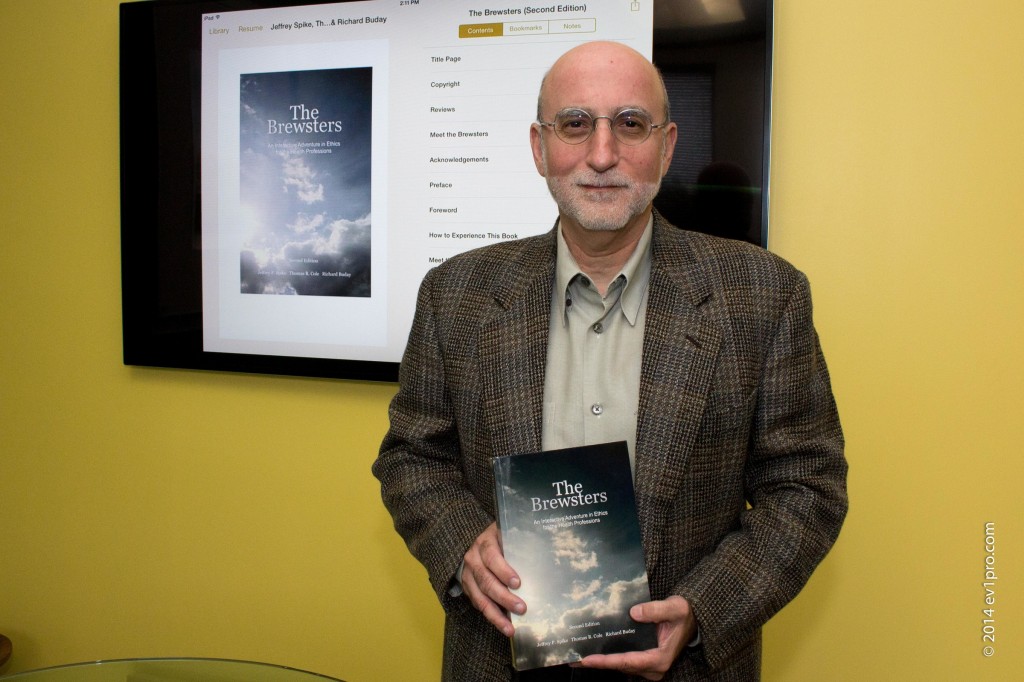

To do this, UT Health asked bioethicists, physicians, attorneys, researchers, academic deans, and public health faculty to weigh in on the contents. And to weave that material into a game-like experience, they hired Richard Buday, a video game designer whose Montrose company Archimage has established itself as a national leader in an emerging field of interactive media called Games for Health, which takes the ideas of gaming and applies them to serious medical concerns.

Trained as an architect, Buday happened into game making. In the 1980s, when his firm was a two-man startup, Buday and then-partner Dwayne Wells invested in a few computers for design work and soon became experts with their new tools. Wells passed away in 1990, and in the years following Archimage dabbled in TV commercials, animated trade show presentations, and the CD ROM vogue. In 1994, they worked on a hugely popular dinosaur video game, and were dubbed national video game experts.

Then in 2003 Archimage was commissioned to create a pair of computer games aimed at helping prevent childhood obesity and Type 2 diabetes. Drawing on the expertise of the Children’s Nutrition Research Center of Baylor College of Medicine, Archimage came up with Escape from Diab and Nanoswarm: Invasion from Inner Space. The games won a bevy of awards, and received extensive clinical testing by Baylor. They also helped Archimage find a new focus: using the techniques of interactive gaming to promote healthy behaviors. Or, as with UT Health, promoting ethical decision making by medical professionals in training.

“Games stimulate ethical practice in a safe environment,” explains Archimage’s Buday. With The Brewsters, Archimage produced a print book and ebook rather than an interactive game for one main reason: cost. Their budget was $100,000, whereas interactive games can cost millions.

But the book format also reflects Buday’s research and experience. “I think the lower the fidelity you present, the better fidelity someone can create in their minds,” he says. “High fidelity presentation decreases the amount you yourself invest. You’re more observer.”

The Brewsters is certainly engineered for investment. The character John Guerra, for instance, “is a 25 year old third year medical student. He was born in Houston to a working class family and received a scholarship to Emory where he graduated with a BS in biology.” In a chapter about professional ethics, Guerra sees his medical school classmate, Walter Brewster, drunk at a party. “TURN TO PAGE 79 TO TAKE WALTER’S KEYS,” the book instructs. Alternatively, “TURN TO PAGE 128 TO LEAVE WALTER TO HIS OWN DEVICES.” But in both plot lines Walter gets hold of a key anyway and crashes his car. The lesson for medical professionals? Even ethical conduct can have bad outcomes. The book’s unpredictability, students say, is one of its appeals.

“This book creates very realistic scenarios and brought up points I hadn’t considered before,” medical student Noor Alzarka told a UT Health writer. “It doesn’t just explore theoretical aspects of health care. There are practical aspects as well.”

Another UT Health student confessed, “I made the wrong decision just to see what would happen.”

Twenty years ago, choosing a game developer to create a teaching tool would have raised eyebrows. It can even do so today; in October, U.S. Representative Andy Harris wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times complaining in part that there were “too many grants going to things like creating a video game for moms to teach them how to get their kids to eat more vegetables.” Why were institutions such as the National Institutes of Health paying to amuse people? The answer, says Buday, lies in the flicker of cave fires and in the adrenalin of a mammoth hunt. We evolved, he says, to learn through doing.

“There’s a certain part of our brain where data goes when you are being told something. It’s the short-term memory section. But when you’ve learned from experience, as in the school of hard knocks, the information goes into the permanent memory section,” Buday says. “As a species, we learned that teaching your Cro-Magnon son about building a fire had a different impact that showing a PowerPoint ever would.”

Play, we know, is especially vital to learning, though the how is not yet fully understood.

“It’s finally starting to become an effective research agenda,” says Buday. ”Fun, apparently, is a real motivator to do things that are good for us. If the learning experience is fun and positive, you’re more likely to pay attention.”

For more than 755 UT Health students who met the Brewsters, the fun has seemed to work. In 2012, according to UT Health, only 69.5 percent of first-year students could analyze ethical components of a research study. After reading The Brewsters, 93 percent of those students could. Similarly, only 83 percent could at first analyze the ethical problems in taking a gift from a drug representative. After reading the book, that number rose to 96 percent.

Will the Brewster clan be as memorable when these students go on to their professional careers? No one yet knows. But if UT Health and Buday are right that emotion lingers beyond lectures, there is reason to think the lessons will stick.

Two years ago, in one of many test-drives of The Brewsters, UT Health’s dentistry school invited two actors from Main Street Theater to visit in the guise of Wayne and Gloria Brewster. Gloria, the matriarch, had gray hair and glasses and held forth about the motives of drug reps. Wayne, the father convinced that he needed an osteoporosis scan, sipped coffee and described his mother’s cancer treatment. The students had all read the book and eagerly quizzed their guests on details of their medical experiences. Most didn’t grasp that the book, and their visitors, were fictional.

“At the end, when they found that Wayne and Gloria were actors, they were angry. Really angry,” Buday says. He smiles with satisfaction. “They cared about these characters. And they were really invested in what happened to them.”