Lines of Communication: LCI Houston Schools Foreign Executives and Students in the Words and Ways of America

Behind a clear glass door on a tranquil Montrose street, voices murmur in languages from around the globe: German, Russian, Arabic, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian. Mixed with each is a more familiar tongue, at least in Texas: English. It’s another day at Language Consultants International Houston, a business dedicated to introducing newcomers to the U.S. to the nuances of speaking, and otherwise communicating, with Americans.

LCI Houston’s Special Programs Director is Marcela Brave, the daughter of an Argentine diplomat who spent her childhood in India, Russia, the Philippines, and Canada. Brave now considers herself a Houstonian, both because of the emotional bonds she’s established in two decades here – a husband, four children, participation in arts groups and theater – and because of her conviction that coming from abroad is in many ways the quintessential route to seeing Houston as home.

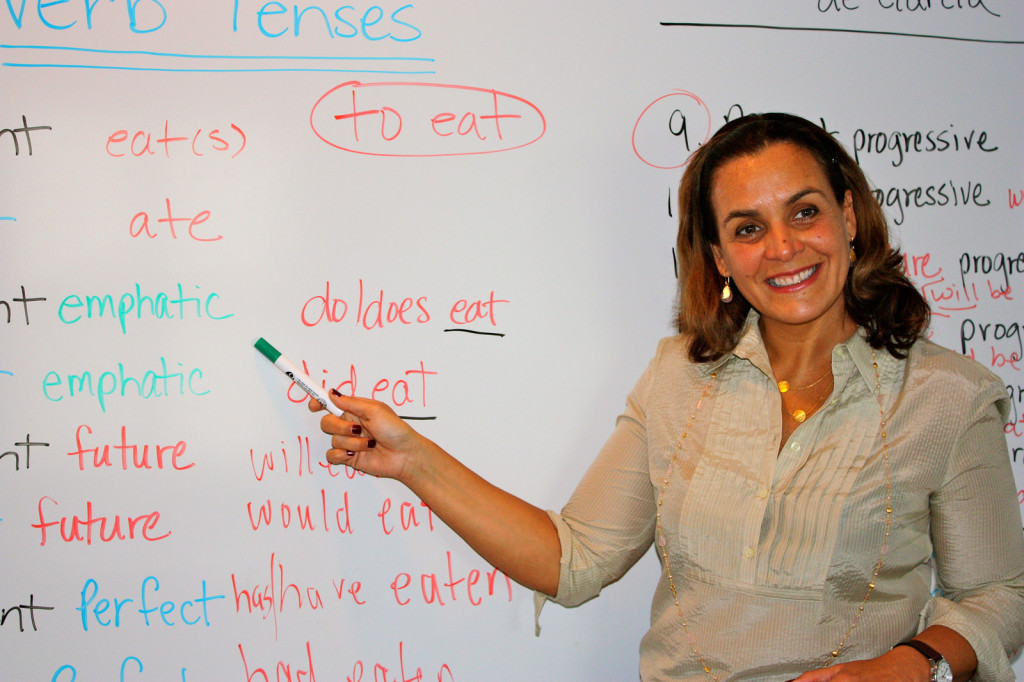

At LCI Houston, teachers strive to make students proficient enough in English to succeed in corporate offices, universities, and testing centers. LCI students can choose from five different programs: Academic English, which prepares adults for a four-year American university; General English, either to wade into the language for the first time or improve skills acquired years ago; Test Preparation, which trains foreign students to navigate the maze of U.S. exams; Executive English, which helps businesspeople improve their English; and Specialized Private Classes, which can be customized to individual needs. At the same time, details ranging from its staff to its Montrose location further a less tangible instructional goal: helping students connect personally with American culture.

We asked Brave to tell us about both the language and the cultural sides of LCI Houston’s work.

How did LCI Houston start?

My brother had been working for a competitor in Denver. He first worked for the company in Argentina, then they invited him to be the administrator at its home base in Denver. They parted ways, and my brother then found a small company that was accredited and doing the same kind of work. He bought this other company and set up LCI. It expanded to Florida, Pennsylvania, and Kansas City. A couple of years ago my sister, who also lives in Houston, says, “Houston is a great place. Why don’t you move here?” We were hoping that he would move the company here. He said he wasn’t leaving Colorado. But he set up a branch here in 2012.

What does LCI do?

It offers opportunities to acquire a second language. Most of our students are international, taking classes to improve their English proficiency so they can enter or attend U.S. universities.

Then there’s our special program, which deals with international executives. We call them immersion students, and most are sent by their companies. These students come here for one to three months. They go back to their businesses at home with a better command of English. The full immersion is incredibly intense. Sometimes it’s a little bit crazy.

Right now, for example, we have a Japanese student in the program. He has eight hours of daily face-to-face instruction time, and two to three hours of homework. He’s exhausted. It’s good that he’s incredibly charming. Last week we took him to Rice’s Glasscock School of Continuing Studies for a networking event. One of the things we talked about was strategies with American business cards. In Japan there’s a very formal ritual around exchanging cards for business. We told our student, “In this country, you may want to grab a beer or go to a baseball game with someone – the business may take place at the end of the day.”

So we gave him a task. We told him he had to meet at least three people and exchange cards and invitations. From that experience, he received three Linked-in invitations.

The most fun part of the event was the social interaction. We had to join a team and build this freestanding structure with dried spaghetti and string. The winner would get a group gift certificate. One of two ladies from Shell was very keen on building the best structure and immediately began working on it. Our student asked, “Should we not work as a team?” In Japan, everyone would have been focused on the team. Following his prompt, we gathered all the participants and each contributed in his own way to eventually win the challenge. That’s the beautiful thing: we get to learn at least a little about how business is done in Japan.

So you deal with cultural competencies as well as language skills?

One of the things we teach our students is that most Americans won’t feel comfortable talking about religion, sex, or politics. I had a young man from Kazakhstan and a young woman from Brazil who were really good friends. Both were married, but they had bonded and become good friends in class. One day, I asked each student to tell about a plane accident they remembered. She mentioned 9/11 and said, “I don’t understand why the U.S. government allows Muslims in the country.” It had not dawned on her that her great Kazakh friend was Muslim.

His English was not as advanced as hers and he didn’t fully understand what she was saying. So she explained. His face changed. The whole tone of the class went down. That class ends, and he says to me, “I don’t want to be in class with her.” I said, hold on, please give this a chance. The next day, I said, we’re going to do conflict resolution, because of the rich diversity in the United States we need to practice conflict resolution. After about 35 minutes of talking, they were friends again. She was crying, it was such an emotional experience. But agreement was reached to not discuss religion.

Why did you choose Montrose?

The school needed to be in a neighborhood that was not only walkable, but also safe, and with character. Houston is a city in which you need a car; Montrose, however, is easy for pedestrians. Character – that’s something difficult to describe, but for a lot of international students, it makes this area feels like home. If you go to the suburbs, you may not see people on the streets, interacting with each other, walking around. If you’re coming from abroad, these things are important.

And if you dig a little deeper, you can go to places like the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum. You can go to the coffee shops. We take our students to KPFT to show them what local radio looks like. The Holocaust Museum and Asia Society are more international in flavor. For better or worse, once our students get used to Houston, they are always incredibly sad to leave for other cities. “Houston is my home away from home,” they’ll say.

We have some much larger competitors in Houston, including ELS, which is part of the Berlitz group. ELS is housed in Montrose too, near the University of St. Thomas. But maybe because we’re smaller, we’re not much of a threat to them, and we send each other students. That’s a Montrose way of business: friendly competition.

Do students from conservative countries comment on the gay culture they see in Montrose?

Well, homosexuality is banned in Saudi Arabia. And we have South Americans who are very Catholic. They’re not unaware of Montrose. But we don’t encourage these conversations in class, unless we feel the students are prepared for a compassionate talk around topics they’ll likely disagree with.

I have to admit, we have not had to manage this issue with our students. In fact, we’ve never had a cross-cultural altercation. Instead, we have had Brazilians, Saudis, and others who have had altercations with other students from their own groups. My theory is that they know the rules with each other, and this provides them a measure of safety.

Tell us about your staff.

It’s very international. Our student advisor, for example, was born in Sudan, and her parents are Armenian. She speaks Armenian, Arabic, and French among others. I met her in a karate class!

Our education coordinator is from the Midwest, but he’s traveled everywhere. Our special programs coordinator is also very traveled, and holds several passports although she was born in Germany. These are individuals who love to travel. Those kinds of passions bring people together. We also have a larger staff than is typical – nine full-time staffers altogether. Most language centers try to keep staffs small, but we keep our staff bigger for better quality. We have 140 students and more than 20 instructors. The instructors work full loads but are not full-time staffers.

Where do most of your students come from?

More than 60 percent are sponsored by the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission. Since 2002, this program has sponsored Saudi students in the U.S. to improve Arab American relations. They have set up this type of cultural mission all over the world.

The Saudi women students are amazed by their experience here. They’re usually our best students. But we have to be very careful; there are a lot of stereotypes about these foreign students. There will be overt prejudice sometimes.

We had a sad story with an immersion student who was a Bedouin. He didn’t enjoy his experience in the United States and decided to leave early. He was not adjusting very well. On his last day, we suggested he go to the Children’s Museum. He visits, leaves the museum, and goes back to his host family. An hour later, the FBI knocks on the door. Someone at the museum had reported our student as suspicious. He was about to get on a plane to go home, so he was dressed as a Bedouin. The police searched him and searched his room. They said, “You can’t leave this room until you go to the airport.” He was petrified.

Tell us about your other students.

If you ever wanted to do a sitcom, you could do one called “Language School.” There’s humor, there’s drama, there’s sadness and tears. There are babies being born. What our students fear above all is any violation of their visas and being deported. The moment that someone doesn’t show up for their scheduled hours in school, we alert Homeland Security.

As an organization, we are closely tied to world events, including conflicts. For example, a recent cohort of students from Iraq has not arrived because of the current conflict there. Some of our students have to hurry home to help their families. It’s heartbreaking because they know they may not come back.

I think they always come away changed personally. The host family of one of our students is very Christian, while our student is a practicing Muslim. He was very close to them. One day he came back to the school to visit and mentioned that he goes to church with the family every Sunday. Then he volunteers with their church to tutor undocumented immigrants.

We encourage volunteerism. It helps students practice English in an authentic setting. It gives the chance to offer something of value. And it conveys the American cultural value of volunteerism. We’ve collaborated with the Houston Food Bank, we may collaborate next with a community garden. And the students ask me, “Why do Americans do this for someone they’ve never seen before?”

What insights do you want your students to leave with?

This is totally personal, but I want them to have the possibility of seeing a world more complex than they could imagine. Suddenly they get to hear a voice they have never heard before, see a face they have never seen before, especially if they come from a place where people traditionally stay put. Secondly, a lot of American culture is stereotyped in the foreign media, and I want our students to learn about some of the contradictions. Whether I talk to native-born Americans or foreign students, and ask them to name things that are American ideals, the ones they name are pretty consistent: freedom, democracy. But our students also see that we have injustice here: toward African Americans, toward the homeless.

Anything new for LCI’s future?

We get a lot of walk-ins from busboys and waiters who want to learn English. Some have been here for eight or nine years, and they know they can’t get promoted unless they learn the language. Unfortunately, they can’t afford our school. Yet the businesses in Montrose have enough non-English speakers that we could get federal funding for free classes in English as a second language.

We interviewed a teacher for this just recently. And I have found someone to write us a grant proposal to fund both English and citizenship classes. There wouldn’t be any profit for LCI. We’re closed in the evenings, which means we could have night classes. Immigrants who work during the day could come to those. As one of our teachers said: “We need to do right by this group of people.” We’re working on it right now.